Liisa Häikiö& the ORSI consortium

Abstract: An eco-welfare state & a just transition

In the coming decade, societies must adapt their activities to meet environmental limits in order to address the challenges of climate change and biodiversity loss. At the same time, they must ensure that the political solutions and measures taken are socially acceptable and just. The welfare state must transform into an eco-welfare state. This is a significant global challenge. No state has yet proposed a credible plan to implement a just transition of this nature and to reach the goals of sustainable development.

Very little knowledge exists about the practical implementation of a transition into an ecologically sustainable welfare state. Our goal is to produce information about the potential of impact-based policy instruments and innovation practices to make the Finnish welfare state environmentally sustainable in a just way. In addition, we examine the ways in which new policy instruments change the normative and ethical foundation of decision-making. What kinds of paths and scenarios do they open for the transition into an eco-welfare state? The main themes of our research are transformative governance and budgeting, a just transition in the everyday life of citizens, responsible innovation processes and regulating consumer choice.

How to make a society environmentally sustainable in an effective but just way?

Finnish society is an international success story by many measures. The creation of the welfare state has led to an increase in education levels, life expectancy and living standards, and a decrease in inequality and poverty. In a hundred years, Finland has developed into one of the richest countries in the world. In international comparisons, it is ranked one of the happiest and most sustainable countries. This success, however, has its downsides. CO2 emissions and the use of natural resources are at a very high level in Finland compared to the rest of the world.

Welfare based on the overuse of natural resources weakens the living conditions of future generations. About a third of the earth’s animal and plant species are under threat due to current global trends (Diaz et al. 2019). In many parts of the world, ecosystems indispensable to human wellbeing are crumbling. The main reason for this is global warming. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, restricting the rise of the average global temperature to 1.5 degrees requires net-zero global greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 (IPPC 2018). Finland is committed to this goal. The current government has set a target for a carbon-neutral Finland by 2035 and a carbon-negative Finland soon after that.

The global ecological crisis challenges the Finnish welfare state from two directions. Firstly, the disintegration of ecosystems will have negative consequences on the wellbeing and health of citizens. Those who have a vulnerable position in society will suffer the most. Secondly, society must reform itself in order to address these threats in a just way. Reaching the emission targets will not be possible without a systemic transition which reforms the entire society and its practices. This requires technological changes as well as behavioural and political changes.

There is increasing research on the direction of the global transition and on sustainable goals. Researchers agree that societies should become carbon-neutral or carbon-negative to avoid an ecological crisis. Changes in energy production, land use, living conditions, transportation and consumption are central to that goal. The global sustainable development goals approved in 2015 (Agenda 2030) seek to address these challenges. The phenomenon-driven goals, such as responsible consumption or reducing inequality, are grounded on a holistic approach to implementing sustainable development. The problem is that no country has yet presented a credible plan for achieving these goals. According to an estimate by an international research group, progress towards the goals been very slow (GSDR 2019). Growing inequality and the global waste crisis, as well as biodiversity and climate degradation, stand in the way of achieving the goals. Finland has outlined national sustainability goals and measures in relation to Agenda 2030, but it can do better, especially regarding transformative politics and consistency (Berg et al. 2019).

What is unclear is how governance and policy instruments should change. How can welfare states, which have concentrated on financial and social wellbeing, reform themselves into eco-welfare states which acknowledge ecological limits? In an eco-welfare state, the government creates and implements policies towards sustainability together with businesses, municipalities, non-governmental organisations and citizens. Achieving goals that align with sustainable development requires many system-level changes and the reconciliation of conflicts of interest. The challenge concerns governance and budgeting, as well as public budgeting and public procurement decisions. New types of policy instruments and innovations are also needed to regulate household consumer choices. Active and responsible intermediary actors play an essential role in this transition.

The Orchestrating for Systemic Impact (ORSI) project investigates this global challenge. Our goal is to create an empirically based understanding in order to change the policy instruments and mechanisms of the welfare state in such a way that ecological sustainability can be improved in a just manner. Our focus is especially on how impact-based policies and innovation practices can be applied to steer the transition to an eco-welfare state.

What is known about instruments for transitioning to an eco-welfare state?

Following an awakening concerning the severity of the ecological crisis, the scientific discussion regarding welfare states is envisaging a transition to an ecologically sustainable welfare state. Scholars have discussed the concept of an ecological welfare state and the kinds of changes a transition to such a welfare state would require. Roughly speaking, the discussion is divided, on the one hand, into scenarios of welfare states built on innovations and various ‘green social contracts’ and, on the other hand, into welfare scenarios of ‘post-growth economies’ which radically redefine social institutions. The research has been normative and theoretical in nature.

Previous research on ecologically sustainable welfare states offers insights into the nature of social change and the ethical and normative foundations of a systemic transition. While the issues underlying welfare states have traditionally been related to social risks and the management of market deficiencies, an eco-welfare state places ecological issues at the heart of politics (Meadowcroft 2005). The goals of ecosocial politics are to increase justice and equality and achieve ecological sustainability (see, e.g. Hirvilammi and Helne 2014; Gough 2017). A political transition that requires the mitigation of climate change sees states as key actors, both nationally and globally. Their central mission is to create conditions for the creation of a carbon-free economy, carbon-free production and consumption, and to ensure the equal distribution of wellbeing (Gough 2017). Cities, local communities and individuals are especially seen as the safeguarders of future wellbeing and also as important drivers of change.

Empirical research on the topic is scarce, however, which is why limited knowledge exists concerning the practical implementation of a transition to an ecologically sustainable welfare state in the context of existing welfare states. The implementation of systemic change, for example, has received little attention. Nevertheless, a transition to an eco-welfare state requires broadly inclusive and cross-governmental political steering that permeates through different levels of government. The transition must take place simultaneously in public administration, economy and finance, among individuals and collectives, and in science and technology. Achieving sustainable development requires coordinated actions between different actors and cross-governmental consistency (GSDR 2019).

Transitioning to an eco-welfare state also necessitates that innovation policy is directed towards sustainability goals and guides innovation processes based on this starting point (Weber & Rohracher 2012). In recent years, innovation research has acknowledged the inadequacy of public governance in addressing big social challenges. Multidisciplinary research on governance practices and innovation processes shows that a transition to an ecologically sustainable society is slowed down and obstructed by siloed operational structures and the failure of existing innovation processes to address social challenges.

The tensions between institutional governance and innovative policy instruments that take advantage of networks complicate or prevent a sustainable transition (Bäcklund et al. 2018). Conflicts arise because, on the one hand, network-based development projects are supported but, on the other hand, resources are distributed among traditional government sectors (Anessi-Pessina et al. 2016; Mauro et al. 2017). Public sector budgeting is an important distribution mechanism for public funds, and it allows public organisations to exercise their accountability to citizens (Schick, 2014). Individual policy measures or societal solutions may have conflicting impacts from the perspective of sustainable development. For example, an effort to curb emissions through high energy taxes will weaken the status of low-income households without creating an incentive for high-income households to reduce consumption. On the other hand, measures to reduce poverty or increase employment may involve economic growth or activities which increase adverse environmental effects. The main objective of innovation activity is to address consumer-driven demand in new ways. Research has also focused on the negative externalities of innovation activity, such as adverse environmental effects and growing inequality (Schot & Scheinmueller 2018). As a result, innovations are often ‘redundant’ from the perspective of societal reform. Innovation activity in itself can also negatively impact on the environment.

We generate knowledge about the significance and potential of policy instruments aimed at societal impacts

Our research project seeks to start a new scientific discussion. In this discussion, views and theories concerning the ecologically sustainable reform of the welfare state are combined with research on social governance and policy. By combining existing data with empirical research and social dialogue, we develop ways to steer the Finnish welfare state towards living within environmental limits.

A promising approach and solution to the social conflicts that arise during the transition is impact-based governance, which transforms long-term political objectives into concrete social impacts. Individuals or clusters participating in governance practices seek to identify innovative solutions to achieve these impacts. The goal of all activity is to generate clearly outlined, definable and measurable impacts (Mazzucato 2018). Impact-focused research has mainly centred on assessing how target setting can improve process efficiency. The eco-welfare state approach, on the other hand, is interested in also assessing impact from the perspectives of social justice and democracy. A new type of governance creates space for new actors, governance processes and policy instruments. A change in governance also changes the distribution of power and responsibility.

Our special interest is on the significance and potential of policy instruments aimed at the societal impacts required to implement sustainable development. In pluralistic societies, political decision-making requires the acceptance of dissent and of the fact that there will always be disagreement (Mouffe 2013). It is important to understand why people have differing opinions.

When implementing systemic change and new approaches, several actors must come together across administrative boundaries. This requires intermediaries and orchestration. Orchestration refers to the mobilisation of actors and networks, collaborating in joint political objectives, and offering conceptual and material support. The orchestration of a transition requires a better understanding of how stakeholder groups are formed and are able to contribute to shared objectives in multi-actor networks, operating on various levels of society at the same time. We approach orchestration as an empirical question: What do different types of governance practices mean for different types of actors? How can different actors contribute to the definition and practices of a just transition and an eco-welfare state?

We generate empirical data and tools to help the state, together with other actors, steer society towards an eco-welfare state in a just and efficient way. Our goal is for this ecological structural change to become a transformative force that would promote social cohesion and increase participation opportunities for citizens. At the same time, we empower individuals, communities and organisations to create or contribute to sustainable societal solutions in everyday life and in decision-making. We offer solutions that enable a socially just transition into an ecologically sustainable society.

The project invites new actors to participate in the change process. The goal is to stimulate a social desire for change which would meet the goals of sustainability and help steer the Finnish welfare state towards living within environmental limits. If the governance of transition ignores the needs of different demographic groups and potential negative effects on inequality, the consequences may manifest as escalating poverty, a rise in extreme ideologies or growing hostility towards opposite viewpoints. The project generates new insights into the normative foundation and the ethical practices of ecosocial policy. The ORSI project studies the transition to an eco-welfare state through four themes: transformative governance and budgeting, a just transition in the everyday life of citizens, responsible innovation processes and regulating consumer choice. We have the following scientific and social objectives:

Transformative governance and budgeting: From objectives to action

Our aim is to influence national and local governance to adopt policy instruments that would generate the tangible social impacts required to implement a sustainable transition. We offer information on impact-based policy instruments, which increase the ability of the state and municipalities to advance a just transition in an efficient way.

We investigate examples of Finnish and international frontrunners at the state and local levels. In practice, we study comprehensive political measures, such as climate legislation and the roadmap to the circular economy, as well as ways to promote sustainable development, for instance, by improving metrics.

With respect to budgeting, we explore a transition to more long-term, cross-sectoral budgeting practices. The goal of the ORSI project is to make sustainability goals a priority in public sector action and financial plans. Instead of making sustainability goals dependent on financial conditions, they should be the starting point for action and financial planning. We seek to promote the achievement of this goal by developing long-term, cross-sectoral budgeting techniques together with state and municipal representatives in particular. One topic of interest will also be the Helsinki–Tallinn Tunnel project, which, if implemented, has the potential to promote the sustainability of the Finnish transport sector.

We acknowledge the central role public procurement plays as a producer of sustainable and high-quality services and an enabler of sustainable consumption in society. Public procurers should be encouraged towards sustainable procurement. One approach could be impact-based procurement, which focuses on environmental and social impacts and which enables a more even distribution and the better management of potential procurement risks. In Finland, the KEINO consortium promotes innovative and effective public procurement.

We focus on important intermediary actors operating on different levels. As an example, we investigate the ways in which effective practices identified by municipal peer networks on climate action, such as the Carbon Neutral Municipalities Network Hinku, are implemented in other public-sector activities related to sustainability.

Together with our partners, we develop policy instruments and principles for implementing ambitious sustainability goals and promoting their acceptance by different actors. Among other things, we will generate recommendations for drafting and measuring comprehensive programmes, best practices for intermediary organisations which will support social change and sustainable budgeting tools for national and local levels.

A just transition in the everyday life of citizens: Strengthening agency and reducing inequality

Our goal is to make sure that the actors who contribute to the transition are informed of the ways in which a democratic and just transition to an eco-welfare state can be implemented. We support this development by producing easily digestible information on impact-based policy instruments which strengthen the agency of individuals and communities in the transition and reduce social inequality.

Our activity is focused on cities. City organisations and active citizens have assumed a central role in the pursuit of sustainability measures. The goal of cities is to make the everyday life of citizens more ecologically sustainable, whereas the goal of citizens is to influence decision-making and planning in their city. In many post-industrial cities, environmental investments have been driven by financial interests, and social issues have taken a back seat. This is especially evident in Nordic countries, which regard social sustainability as a given (Terama et al. 2019). However, investments into sustainable development may in some cases have even increased inequality within cities (While et al. 2004). Both authorities and citizens are facing a difficult challenge. Creating a consensus or building collaboration in order to pursue sustainable development requires the convergence of several stakeholder views (Häikiö & Lehtonen & Salminen 2017; Wallin et al. 2018).

We explore the ways and the policy instruments which would enable the transition to an eco-welfare state to be implemented in a way that is socially just and increases participation. We also investigate the ways ecosocial policies manifest in people’s everyday lives. For example, how are the needs and vulnerabilities created by various life situations acknowledged when drafting new regulations? Are individuals and networks willing or able to contribute to societal change? How does grassroots citizen activity affect change on different levels? How are power, responsibility and resources distributed in new ways when different policy instruments are introduced? In practice, we study sustainable development in the City of Lahti and the Lappeenranta region, the development of the Hiedanranta neighbourhood in Tampere and social sustainability development activities carried out in different cities.

We investigate the conflicts that can arise from changes towards an environmentally sustainable society and the ethical and democratic principles that can help in solving them. We combine everyday empirical research with normative theory development (Herzog & Zacka 2019). We develop the ethical and social understanding that is required to govern an eco-welfare state from the perspective of people’s daily lives. We acknowledge people’s diverse life situations and their opportunities to contribute to change. Together with our partners, we create guidelines and tools for decision makers which are based on democratic and ethical principles and which enable a just transition to an eco-welfare state.

Responsible innovation processes: From competitiveness to societal solutions

Our goal is to change our shared understanding of innovation activity and its social significance. Instead of offering competitive advantage, the innovation processes of an ecologically sustainable and socially just society must offer practical solutions to social problems. A transition to an eco-welfare state requires innovative approaches to organising key societal functions. The task of public decision makers is to support the development of sustainable practices and technologies. In responsible innovation processes, innovation is not solely motivated by financial objectives but by broader social impacts, and it acknowledges the values and views of societal actors.

Until now, research on responsible innovation processes has focused on critical analyses of traditional innovation policy, creating new evaluation frameworks and normative goals for innovation policy (e.g. Weber & Rohracher 2012). In terms of practical policy instruments, innovative public procurement has been employed to advance societal transformation (Uyarra et al. 2020). In addition, methods for collaboration between social groups have been developed in order to build future visions and goals (Nieminen & Hyytinen 2015). However, internationally there are a limited number of practical examples of impact-based policy instruments that promote responsible innovation activities. Our aim is to increase understanding of both the best practices in individual approaches and the change in logic regarding the role of innovation policy and innovation processes in practice.

We examine the expanding role of innovation policy, expanding from promoting competitive advantage to solving social challenges. We investigate how responsible impact objectives are drafted and adopted in collaboration between various actors, new forms of cooperation between the public and the private sectors, and the coordination of impact on different levels and domains of governance. We focus on new public policy instruments aimed at promoting responsible innovation activities and a system-level transformation towards an eco-welfare state. We study changes in the logic of decision-making, the tensions involved in reconciling different objectives, and practical approaches and their implementation. In practice, we examine innovation processes related to, for example, innovative public procurement, impact investments, innovation competitions, the project alliance model and regional development projects.

Together with our partner organisations, we build understanding on the potential of impact-based policies to promote the creation and implementation of socially, environmentally and financially sustainable innovations. We generate descriptions and recommendations on the pro-innovation approaches and best practices required to achieve impact objectives.

Regulating consumer choice: Lifestyle choices, new actors, new tools

We produce knowledge which can help societal actors to create more diverse policy measures with which to target individual choice and to extend the regulation of consumer choice to everyday structures and questions of justice. Our goal is to promote sustainable and systemic lifestyle choices through expanding opportunities for participation and engaging new actors. The impact is reflected in the ways in which new actors contribute to the regulation of everyday choices.

The research is grounded on the idea that a sustainable lifestyle is an interaction between everyday choices and the actors that influence them. Emphasising consumer choice in the politics of sustainable development leads to unrealistic and unfair expectations regarding the ability of consumers to steer social change (Akenji 2014; Wiedenhofer et al. 2018). Reducing the carbon footprint of households necessitates cutting consumption, improving efficiency and other changes in consumption behaviour. Infrastructure and political decision-making may offer instruments with which to change consumer choices. Removing everyday obstacles requires systemic changes and political steering instruments (Lettenmeier et al. 2019). On the other hand, everyday changes and the analyses, experiments and future scenarios regarding those changes support the development of possible broader and systemic changes (Laakso & Lettenmeier 2016).

We study the distribution of the use of natural resources and consumption opportunities in Finnish society, as well as digital tools and online environments whose goal is to spread information and help people transform their daily lives so that they involve sustainable and fair consumption. In concrete terms, we examine carbon footprint calculators and personal carbon budgeting tools, such as Sitoumus2050, and experiments that promote everyday changes, such as international sustainable lifestyles accelerators. Our inquiry focuses on the administrators and users of these tools and environments, as well as on the new types of relationships and orientations created by these tools and environments. Our partners include both municipalities and businesses.

We develop tools for regulating consumption with a special emphasis on issues concerning the fair distribution of consumption opportunities and the broader systemic conditions for changing private consumption. We follow the workshops of sustainable lifestyles accelerators, which will inform the development of criteria for a good carbon calculator. We develop digital and visual tools for carbon budgeting and other purposes.

Social and multidisciplinary interaction

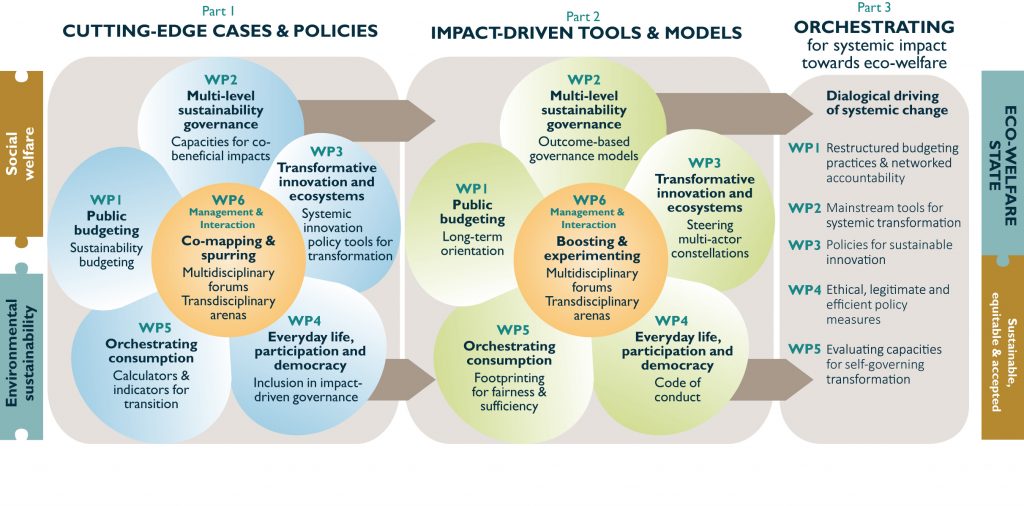

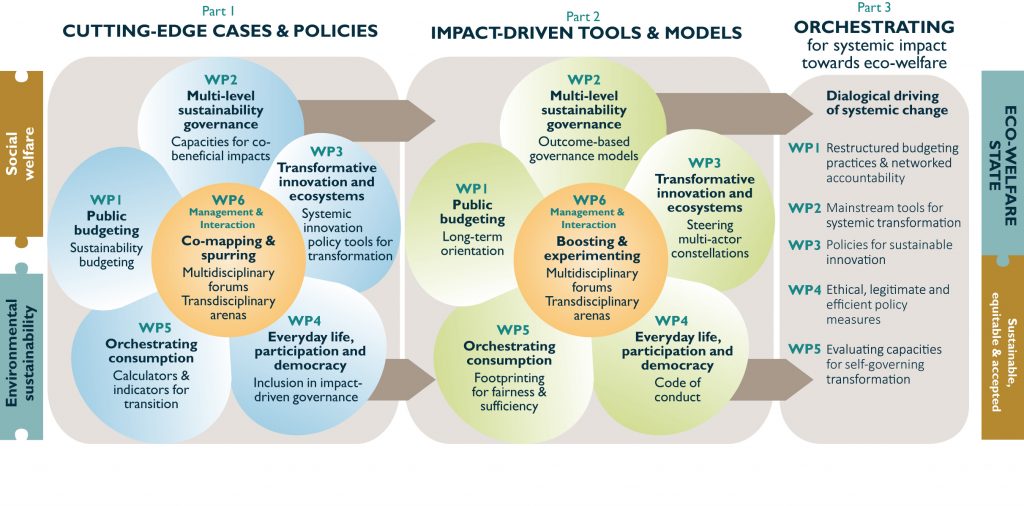

The project is divided into six work packages (see Figure 1). The work packages act in collaboration with three interconnected research areas.

Figure 1. The implementation of the ORSI project.

In the first part, we map cutting-edge cases and policies. The cases and policies under study represent two distinct governance approaches for creating social impact. In one, the aim is to steer individuals’ activities in order to make them pursue ecosocial impacts through their actions. In the other, the aim is to create and steer networks which will promote and strive for ecosocial impacts through collaboration. The mapping and case examination will generate the majority of the project’s research data (e.g. interviews, ethnographic observation, statistics, user testing). ORSI will organise round table meetings and discussions for stakeholder groups in order to explore collaboration possibilities. On Aalto University and Tampere University courses, students will work on themes and policy instruments related to eco-welfare states. The project researchers will contribute to restructure policy measures by lending their expertise to various development forums at organisational, municipal and state levels.

In the second part, we promote and experiment with impact-driven policy instruments through data analysis and co-creation with various actors. We critically evaluate political practices and produce new information to support political decision-making. On the other hand, we influence people’s everyday lives by studying and further developing new methods of participation. Our goal is to identify and strengthen social outcomes that are effective and equitable from the perspectives of various actors and the policy instruments that advance them. We organise forums for forerunners, and seminars and other events for stakeholders and the general public. We will bring actors to roundtable discussions to generate research questions and to reflect on the results of the research together. The project themes are also discussed in dialogues aimed at increasing understanding between different actors. Various actors will be invited to join the dialogues, including political decision makers, business representatives and citizens. Together with their partners, the project researchers will develop impact-based policy instruments, governance models and scenarios. In the third part, we will enable the creation of systemic change by aggregating and developing new, impact-based policy instruments, their ethical principles and their scientific basis. Our goal is to open a new field of research in order to form a knowledge base for the governance of an eco-welfare state and to improve the openly available tools and guidelines that support impact-based policies. In open seminars, our researchers will present the findings and results of the project. The researchers of the ORSI project participate actively in scientific and public discussion related to the themes of the research project.

Bibliography

Agenda 2030 (2015). The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations.

Akenji, L. (2014). Consumer scapegoatism and limits to green consumerism. Journal of Cleaner Production, 63, 13–23.

Anessi-Pessina, E., Barbera, C., Sicilia, M., & Steccolini, I. (2016). Public sector budgeting: a European review of accounting and public management journals. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 29(3), 491–519.

Berg, A., Lähteenoja, S., Ylönen, M., Korhonen-Kurki, K., Linko, T., Lonkila, K. M., … & Suutarinen, I. (2019). PATH2030 – An Evaluation of Finland’s Sustainable Development Policy. [POLKU2030 – Suomen kestävän kehityksen politiikan arviointi.] Publications of the government’s analysis, assessment and research activities 23/2019. Helsinki: Prime Minister’s Office.

Bäcklund, P., Häikiö, L., Leino, H., & Kanninen, V. (2018). Bypassing publicity for getting things done: between informal and formal planning practices in Finland. Planning Practice & Research, 33(3), 309–325.

Díaz, S., Settele, J., Brondízio, E., Ngo, H., Guèze, M., Agard, J., … & Chan, K. (2019). Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.[DJ1]

Gough, I. (2017). Heat, greed and human need: Climate change, capitalism and sustainable wellbeing. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

GSDR (Global Sustainable Development Report) (2019). The Future is Now – Science for Achieving Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations.

Herzog, L., & Zacka, B. (2019). Fieldwork in political theory: Five arguments for an ethnographic sensibility. British Journal of Political Science, 49(2), 763–784.

Hirvilammi, T., & Helne, T. (2014). Changing paradigms: A sketch for sustainable wellbeing and ecosocial policy. Sustainability, 6(4), 2160–2175.

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) (2018). Global Warming of 1.5 ºC.[DJ2]

Laakso, S., & Lettenmeier, M. (2016). Household-level transition methodology towards sustainable material footprints. Journal of Cleaner Production, 132, 184–191.

Lettenmeier, M., Akenji, L., Toivio, V., Koide, R., & Amellina, A. (2019). 1.5-Degree Lifestyles: Targets and Options for Reducing Carbon Footprints. [1,5 asteen elämäntavat: Miten voimme pienentää hiilijalanjälkemme ilmastotavoitteiden mukaiseksi?] Sitra: Helsinki

Mauro, S. G., Cinquini, L., & Grossi, G. (2017). Insights into performance-based budgeting in the public sector: a literature review and a research agenda. Public Management Review, 19(7), 911–931.

Mazzucato, M. (2018). Mission-oriented innovation policies: challenges and opportunities. Industrial and Corporate Change, 27(5), 803–815.

Meadowcroft, J. (2005) From welfare state to ecostate. In J. Barry and R. Eckersley (eds) The State and the Global Ecological Crisis. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 3–23.

Mouffe, C. (2013). Agonistics: Thinking the World Politically. London: Verso.

Nieminen, M., & Hyytinen, K. (2015). Future-oriented impact assessment: Supporting strategic decision-making in complex socio-technical environments. Evaluation, 21, 448–461.

Schick, A. (2014). The metamorphoses of performance budgeting. OECD Journal on Budgeting, 13(2), 49–79.

Schot, J., & Steinmueller, W. E. (2018). Three frames for innovation policy: R&D, systems of innovation and transformative change. Research Policy, 47, 1554–1567

Terama, E., Peltomaa, J., Mattinen-Yuryev, M., & Nissinen, A. (2019). Urban sustainability and the SDGs: A Nordic perspective and opportunity for integration. Urban Science, 3(3), 69.

Uyarra, E., Zabala-Iturriagagoitia, J. M., Flanagan, K., & Magro, E. (2020). Public procurement, innovation and industrial policy: Rationales, roles, capabilities and implementation. Research Policy, 49(1), 103844.

Wallin, A., Leino, H., Jokinen, A., Laine, M., Tuomisaari, J., & Bäcklund, P. (2018). A polyphonic story of urban densification. Urban Planning, 3(3), 40–51.

Weber, K. M., & Rohracher, H. (2012). Legitimizing research, technology and innovation policies for transformative change: Combining insights from innovation systems and multi-level perspective in a comprehensive ‘failures’ framework. Research Policy, 41(6), 1037–1047.

While, A., Jonas, A. E., & Gibbs, D. (2004). The environment and the entrepreneurial city: searching for the urban ‘sustainability fix’ in Manchester and Leeds. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 28(3), 549–569.

Wiedenhofer, D., Smetschka, B., Akenji, L., Jalas, M., & Haberl, H. (2018). Household time use, carbon footprints, and urban form: a review of the potential contributions of everyday living to the 1.5 ºC climate target. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 30, 7–17.